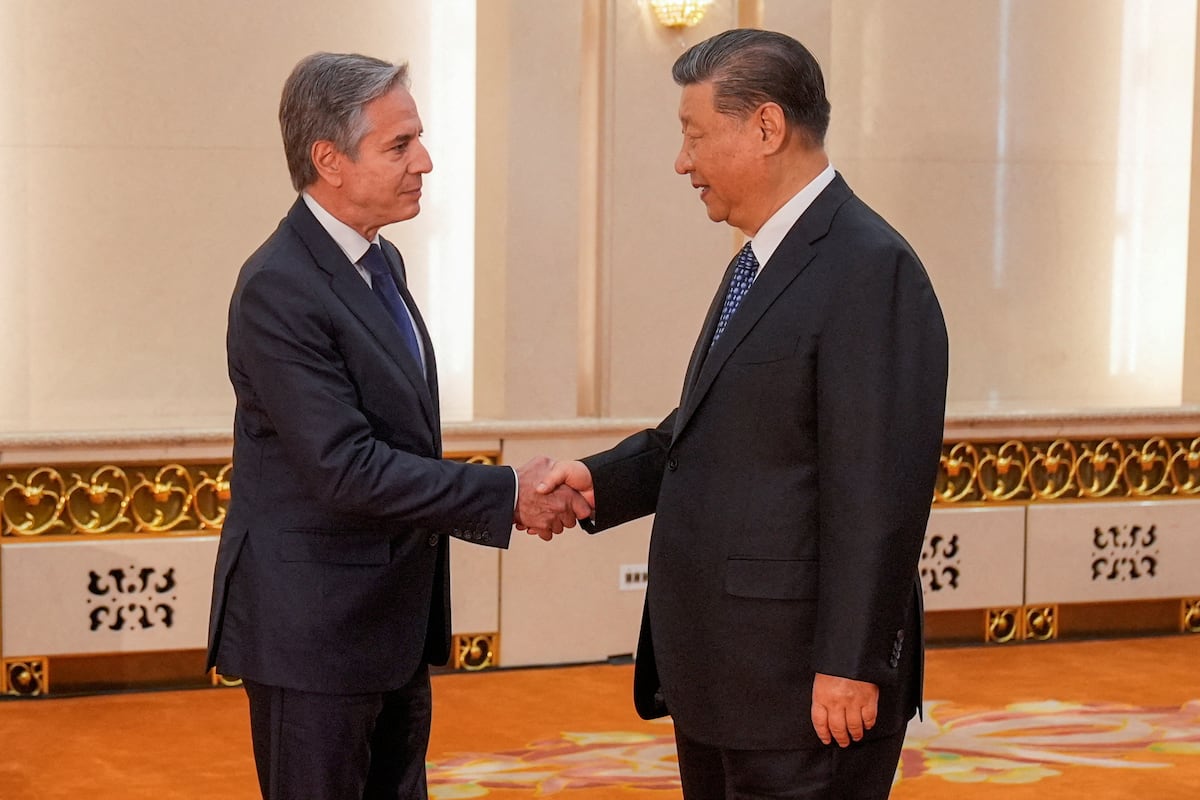

Diplomatic Efforts Renewed: Blinken’s Visit to China Reaffirms Importance of Cooperation in Maintaining Bilateral Stability

During his recent visit to China, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken emphasized the importance of active diplomacy to maintain the fragile stabilization of bilateral ties. The need for cooperation…

Bloat and Indigestion: The Impact of Overeating and How to Alleviate It with Light Exercise, Mindful Eating Habits and Healthy Foods.

Doctor Vu Truong Khanh, Head of the Department of Gastroenterology at Tam Anh General Hospital in Hanoi, explained that overeating can strain the stomach and disrupt intestinal motility. This can…

Swiss National Bank Criticized for Rejecting Activist Investment Policies: Balancing Stability and Change in the Face of Political Pressure

During the General Meeting (AGM) of the Swiss National Bank, attendees expressed their opinions on what changes the bank should make. However, Bank Council President Barbara Janom Steiner turned the…

Argentina Faces Critical Data Security Challenges: Beatriz Busaniche and the Via Libre Foundation Demand More Accountability

In the past two weeks, Argentina has been hit with a series of significant personal data leaks. The first incident occurred when a cybercriminal published over 115 thousand stolen photos…

Ellen DeGeneres Opens Up About Challenges in Personal and Professional Life: Navigating Aging, Loss, and Controversy

Ellen, in her recent interview, compared the cancellation of her talk show to the cancelation of her sitcom Ellen in 1998 when she came out as gay. She jokingly remarked…

Hands-On Science Exploration at Inland Empire Science Festival: A Success Story

The Inland Empire Science Festival held at the Western Science Center in Hemet was a huge success among attendees. Leya Collins, the WSC Museum Laboratory Manager, welcomed visitors with “Charlotte,”…

The Battle Against Monopoly Power: Amazon Faces Legal Action for Antitrust Violations

Amazon, the e-commerce giant that has transformed from a small website for purchasing books to a massive entity that impacts almost every aspect of daily life, is facing legal action…

Shreveport Police Seek Public Help in Locating Missing 59-Year-Old Woman Latonia Wade

The Shreveport Police Department is seeking the public’s help in locating a missing 59-year-old woman, Latonia Wade. She was last seen on April 3rd, 2024, in the 4500 block of…

New Federal Rule Protects LGBTQ Rights in Healthcare: A Step Towards Equality

The Biden administration has announced a new federal rule aimed at protecting the civil rights of transgender and other LGBTQ individuals. This rule, announced by the Department of Health and…

Rising Swimmer Regan Smith’s Eligibility in Question after NCAA Withdrawal

In March, Regan Smith made headlines when she entered the NCAA transfer portal. However, new information has emerged that suggests she has withdrawn from the portal. Athletes in the portal…