Festo and Phoenix Contact Partner to Revolutionize Industrial Automation with Open Architecture PLC Technology

At the Hannover Messe, Festo announced their plans to integrate PLCnext Technology from Phoenix Contact into their upcoming intelligent devices. By combining the strengths of both companies, they aim to…

Oil Prices Dip Despite Middle East Tensions, U.S. Crude Inventories Help Limit Losses

Due to decreased worries over conflict in the Middle East and slowing business activity in the world’s largest oil consumer, oil prices dropped slightly on Wednesday. However, a decline in…

Fastest man on earth joins forces with cricket to promote global tournament: Usain Bolt named ambassador for ICC Men’s T20 World Cup 2024

Usain Bolt, an eight-time Olympic gold medallist and a world record holder in sprinting events, has been named as the ambassador for the upcoming ICC Men’s T20 World Cup 2024.…

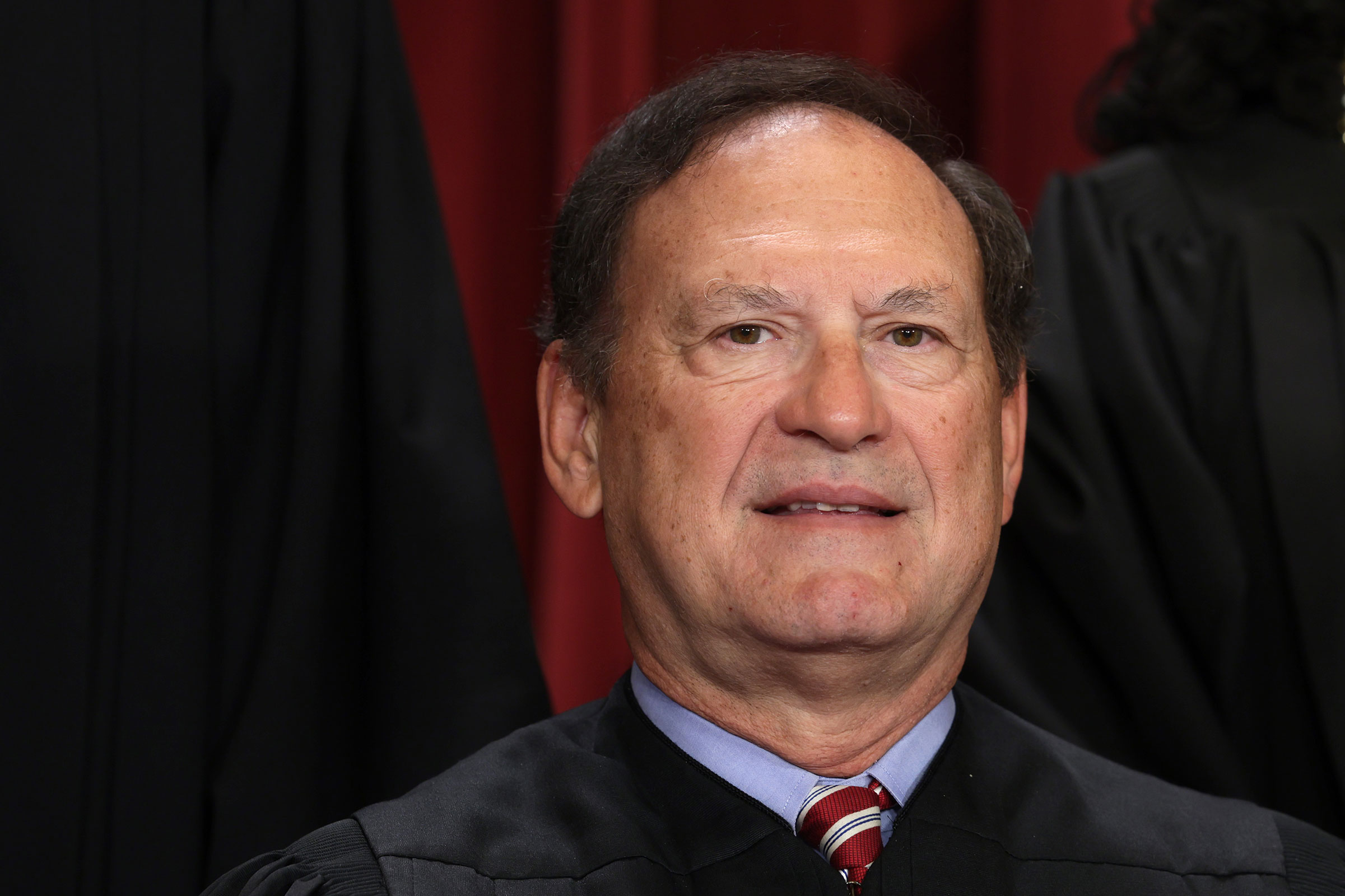

Supreme Court Battle: Female Justices Grill Idaho Attorney on Abortion in Medical Emergencies

During a heated Supreme Court hearing, female liberal justices grilled Idaho attorney Joshua Turner about hypothetical scenarios involving pregnancy complications that pose serious health risks to women. The discussion centered…

Sweeten Your Spirit: Carlsborg’s WeDo Fudge and Cascade Caramel Announce Drive-Thru Reopening with Prayer Services

Carlsborg’s beloved candy shops, WeDo Fudge and Cascade Caramel, have announced their plans to reopen their drive-thru sweet shop. The two companies have joined forces once again to offer residents…

From Outreach to Outstanding: Pine-Richland Students Secure World Championship Spot in FIRST Robotics

Pine-Richland students Ryan Scott, Piya Dargan and Keerthana Visveish recently secured a spot at the FIRST Robotics World Championship in Houston, Texas. As part of the BrainSTEM Learning Giant Diencephalic…

Marrakesh Treaty Implementation Guidelines Enhance Global Educational Accessibility and Inclusion Efforts

The global repository of educational materials has been enriched by the development of Marrakesh Treaty Implementation Guidelines, advocacy materials, and multilingual learning resources. These accomplishments have fostered innovation and advanced…

Towson Senior Swimmer Brian Benzing Hits Academic Highs: Named College Sports Communicators Academic All-America Honoree and 4x consecutive CAA Men’s Swimmer of the Year

Towson senior men’s swimmer Brian Benzing received College Sports Communicators Academic All-America honors for his outstanding performance in the classroom in addition to his achievements in the pool. With a…

Empowering Communities: How Medicaid Expansion Could Benefit Kansas

During a town hall meeting hosted by the Kansas Health Foundation (KHF) in Wichita, Governor Laura Kelly and Ed O’Malley, KHF President and CEO, discussed the importance of expanding Medicaid…

Empowering the Next Generation of Scientists: McGill’s Chemistry Outreach Group and Real Ventures Join Forces to Encourage Diversity in STEM

On March 21st, 2024, McGill’s Chemistry Outreach Group participated in the Real Ventures Future Innovators Science Fair at the Royal Charles Elementary School. The event was held in honor of…