Algae and Bacteria Merge in Unprecedented Evolutionary Event with Implications for Agriculture

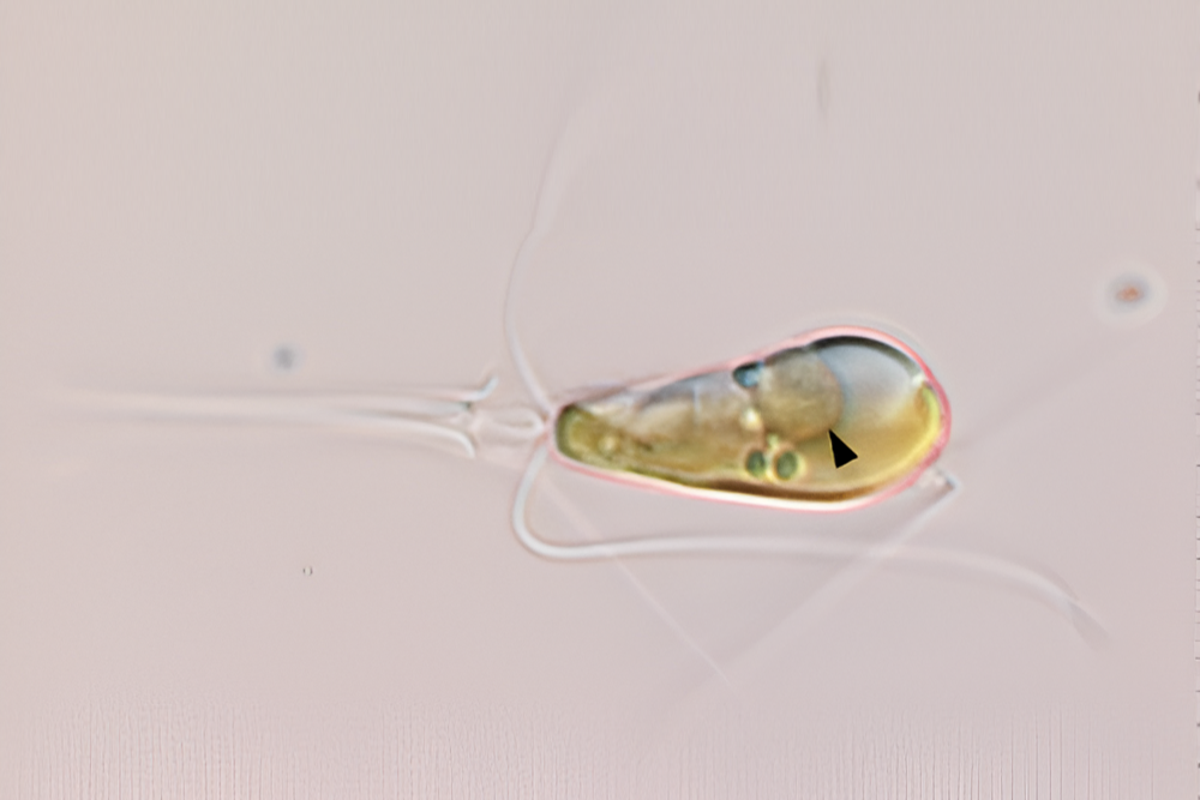

In an unprecedented evolutionary event, two lifeforms have merged to form a single organism through primary endosymbiosis. This process has only occurred twice in the history of the Earth –…

The Great German Work Debate: Balancing Economic Growth with Work-Life Balance

In recent times, German politicians and business leaders have begun to discuss a topic that was once considered taboo: the notion that their fellow citizens do not work enough. This…

LG Electronics Bounces Back: Profitability Returns to TV Business Thanks to Increased Demand and Streaming Services

LG Electronics’ TV business returned to profitability in the first quarter, thanks to the recovery of demand in Europe and the increasing popularity of streaming services. The South Korean electronic…

Revolutionizing Law Enforcement: How Drones are Transforming Miami Township’s Safety and Search Capabilities

In Miami Township, the use of drones has proven to be a valuable tool in enhancing community safety and aiding law enforcement. With only being utilized for about six months,…

10 High School Students Gain Real-World Experience and Technical Skills through Licking Heights’ High School Tech Internship Program

Licking Heights Local Schools is set to provide real-life experience and on-the-job technology training for 10 high school students through a new program, thanks to an investment from the Governor’s…

Meet Kiah Helget: The Unstoppable Greyhound Softball Phenom and All-Around Interesting Person

Kiah Helget, a senior at New Ulm Cathedral, hit a two-run home run against Nicollet on Monday at Harman Park, leading the Greyhounds to a 16-0 victory in just four…

Kidnapped Journalist: A Heartwrenching Tale of Captivity and Hope

Hirsch Goldberg-Polin, a dual citizen of Israel and the United States, was kidnapped by Hamas militants on October 7. The Kan-11 television channel reported that a video of the hostage…

Revolutionizing Retail: Exploring the Benefits of RFID Technology

RFID technology provides more than just inventory accuracy in the retail industry. This report explores the numerous benefits of this technology for retailers, associates, and consumers, as part of our…

World Malaria Day: Uniting for an Equitable Fight Against the Devastating Mosquito-Borne Illness

The observance of World Malaria Day on April 25th is an annual event that aims to raise awareness about the serious threat of malaria, a mosquito-borne illness. This year’s theme,…

World Malaria Day 2021: Fighting for Equity in the Battle Against Mosquito-Borne Illness

April 25th is observed every year as World Malaria Day, which aims to raise awareness about the serious mosquito-borne illness. The theme for this year’s event is “Accelerating the fight…