World Malaria Day 2021: Fighting for Equity in the Battle Against Mosquito-Borne Illness

April 25th is observed every year as World Malaria Day, which aims to raise awareness about the serious mosquito-borne illness. The theme for this year’s event is “Accelerating the fight…

Unraveling the Complexities of Accountability and Human Rights in the Age of Autonomous Intelligences: Challenges Faced by Courts in Integrating AI into Various Sectors

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into various sectors, including technology, law enforcement, and court systems, presents complex issues related to accountability and the application of human rights to autonomous…

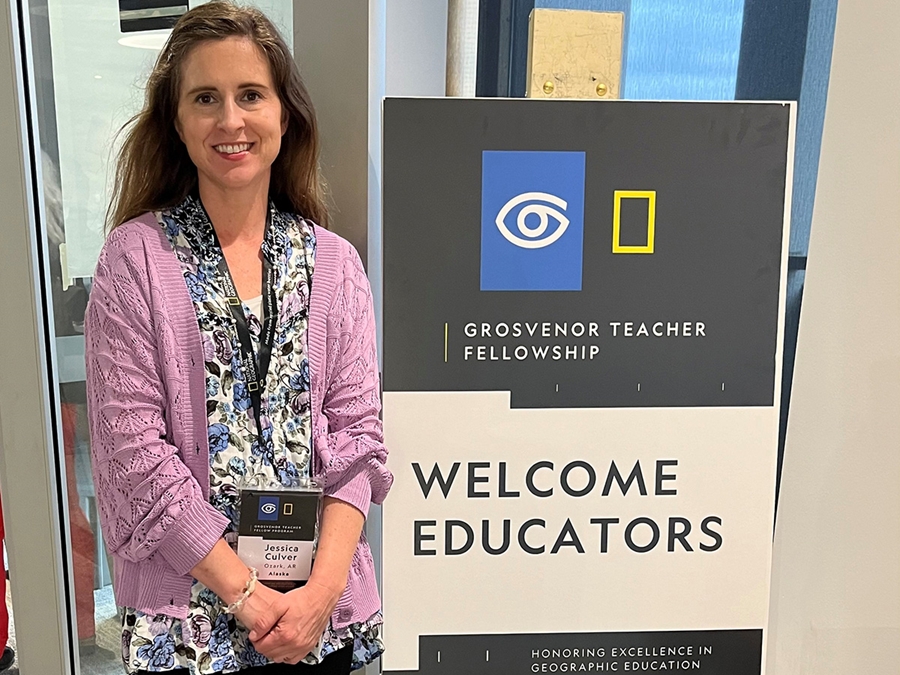

Ozark Teacher Embarks on Epic Alaskan Adventure through Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship Program

Jessica Culver, a doctoral student in the College of Education and Health Professions Adult and Lifelong Learning program, has been selected to participate in the 2024 Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship program.…

Cultivating Knowledge: Beatrice High School’s Greenhouse Sale Showcases Botany and Plant Science Expertise

Beatrice High School’s science club is hosting its annual spring sale this week in the school’s greenhouse. Initiated several years ago as a grant project by Dr. Joan Christen, the…

Raising a Glass: Celebrating Global Excellence in the 2024 World Beer Cup Awards

The 2024 World Beer Cup Awards held at The Venetian Las Vegas on April 24th recognized excellence in over 100 categories of beer from around the world. Organized by the…

Equity and Inclusion in Medical Science: Insights from STAT’s 2024 List of Leaders in the Life Sciences

Wednesday night in downtown Boston, physicians, researchers, CEOs, reporters, and more gathered to celebrate STAT’s 2024 STATUS List. This year’s list features 50 leaders in the life sciences who are…

Navigating the Uncertainties: The Future of Work in Texas and Its Implications for the Nation’s Economy and Labor Force

The future of work in Texas is uncertain, as the state’s economy and labor force continue to change. With over 15 million working Texans, the state has experienced steady growth…

From Flipping to Facelifting: Affordable Kitchen Renovations with FunCycled in Wynantskill

FunCycled, a family-owned business located in Wynantskill, has been providing kitchen cabinet painting and interior design services since 2021. Initially starting as a flipping company, they have since expanded their…

From Frying Pans to Community Spirit: The World’s Biggest Fish Fry Returns to Paris, Tenn.

Paris, Tenn. was buzzing with excitement on April 20th as the 71st annual World’s Biggest Fish Fry returned to town. The event, which is a community-wide celebration and kickoff festival…

Unleashing Innovation in Healthcare: Empowering Teams to Drive Creativity and Growth

A culture of innovation in healthcare is a challenging task, requiring the collective creativity of teams rather than a top-down approach. This on-demand webinar, available for viewing at your convenience,…